Bernard Pietenpol: Father of the Home Built Airplane

A new dawn of mechanical advancement was brought to the forefront of American consciousness because of the burgeoning automobile industry after World War I. Dreamers and adventurers alike were captivated by the use of airplanes during the war. Many Americans were eager to experiment with building their own airplanes or improving motorized aviation technology. Tinkering with cheap and practical home built aircraft became common in garages and workshops in small towns throughout the country. Much like Orville and Wilbur Wright did years before, these trailblazers sought to use the latest technology to forge new pathways in aviation history.

When barnstormers began buzzing dairy barns, cornfields, and cherry orchards in southern Minnesota, a fire was lit within three young men in Cherry Grove. Bernard Pietenpol, Donald Finke, and Orrin Hoopman grew up in a time of meager subsistence and great sacrifice. Their quest to join the golden age of aviation lead them to collect spare parts, build what they could not buy, and experiment with motorcycle, aircraft, and automobile engines in order to create their own home built airplane.

Bernard Pietenpol was a well-known automobile and farm mechanic in Cherry Grove. He had a reputation for being the one person in the area who could repair anything with a motor. In the mid-1920s, Pietenpol began learning how to fly airplanes. At the same time, he worked with his friends to put together an airplane made up of surplus parts that would get them safely in the air. Their first successful design in 1928 used a four-cylinder, 30-horsepower ACE engine that was converted from a discarded Model T engine from Pietenpol’s repair shop. Pietenpol volunteered to make the first flight—but the plane barely made it off the ground.

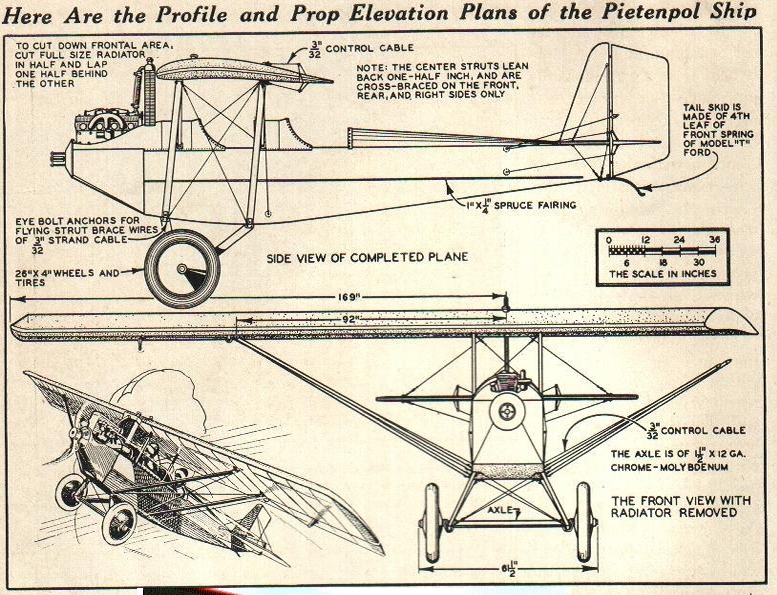

The next attempt at getting in the air didn’t come until the Ford Motor Company produced the Model A in 1929. The 40-horsepower engine in the Model A had twice the power of the converted Model T engine used in the first design. Pietenpol immediately set about acquiring parts to build a Model A engine. Once the motor was built for the aircraft, he mounted it and an older Model T radiator on the 18-foot wooden frame that sported a war surplus Lawrance propeller. The instrument panel included a throttle, airspeed indicator, tachometer, height meter, a magneto switch, and oil and water temperature gauges. The wings spanned 29-feet and were covered with varnished bed sheet fabric. The plane rose six feet off the ground—the tail-dragging skid was made from part of a Ford spring leaf. No tail wheel. No brakes.

Pietenpol christened the aircraft as “The Two-Place”. It took to the air with Pietenpol in the cockpit for the first time on May 20, 1929. It soared smoothly 500 feet above Cherry Grove at 70 mph. From then on, Pietenpol was hooked. He flew The Two-Place every chance he got—including several 250-mile round trips to Minneapolis. Little did he know that his home built aircraft was about to change his life.

Westy Farmer was another aviation enthusiast. His flair for the dramatic led him to write about the blossoming aircraft revolution for Modern Mechanics and Inventions magazine. Working from his office in Minneapolis, Farmer penned several articles encouraging readers to buy manuals for home built airplanes and making suggestions about which parts worked best in the planes.

In a 1929 article about which engines work best in home built aircraft, Farmer firmly stated: “No auto engine can be converted to flight. They are too heavy.” After reading this article, Pietenpol hastened a letter to the editor saying that Farmer’s information was incorrect; automobile engines could be used and Pietenpol was going to prove it to him.

At a large aircraft show organized by Farmer on April 14, 1930, Pietenpol proved his point. The rain grounded all of the scheduled large planes, but Pietenpol landed The Two-Place on a runway just outside of the airfield fence. Curiosity about the aircraft prompted Farmer to scramble across the field in his car. There he met Pietenpol and looked over the aircraft he said could not be made.

Farmer urged Pietenpol to show his aircraft off to the crowd and several reporters in attendance. Pietenpol took to the air as the impromptu main attraction in his home built aircraft and landed to a cheering crowd. The enthusiastic response caused Farmer to feature Pietenpol’s aircraft in the next issue of Modern Mechanics and Inventions. The following year, Farmer helped Pietenpol create a full set of plans for the aircraft that became known as the Air Camper. The plans were sold for $7.50 through the magazine. The simplicity of the design, the availability of post-war aircraft parts, and used Ford engines caused immediate popularity for which Pietenpol was not prepared. He began to manufacture and sell parts for the aircraft for people who didn’t want to scavenge for the parts. Pietenpol moved his shop into the largest abandoned building in town—the Lutheran church.

Pietenpol’s Garage and Workshop became the top employer and a thriving business in Cherry Grove. He enlisted local machinists and mechanics to help keep up with all of the orders he was receiving. As an added convenience for customers who didn’t want to build the aircraft themselves, Pietenpol and his crew would build a complete Air Camper for them for $750. Later, he converted a modified Model T engine for a second home built aircraft available to customers, which he called the Sky Scout.

Pietenpol and his wife, Edna, never moved away from Cherry Grove. His workshop and garage were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981. A hangar he designed was disassembled and relocated to Pioneer Airport in Oshkosh, Wisconsin as part of the Experimental Aircraft Association Museum. In 1984, Bernard Pietenpol died at the age of 83. International aviation historians have dubbed him as the “father of the home built airplane.” He was posthumously inducted into the Minnesota Aviation Hall of Fame in 1991. Today, there are several Pietenpol aircraft clubs throughout the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The Pietenpol family still sells original Air Camper plans—visit the Pietenpol Aircraft Company website for more photos or to view and order Air Camper plans and kits.