Key concepts

Biology

Vision

Pupil

Light

Color

Introduction

Have you ever considered taking a nighttime nature walk? Would you wait until there is a full moon so you could benefit from sunlight reflected from the moon—or would you rather take a flashlight? Do you think trees would look black, green or gray in the dark? Try this activity to examine your night vision and prepare for your next nighttime adventure!

Background

Sight begins when light enters the eye. This light triggers light-sensitive cells in the retina at the back of the eye. As a result signals zoom along the optic nerve to the brain. The brain then makes sense of the signals, giving us the experience of seeing.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

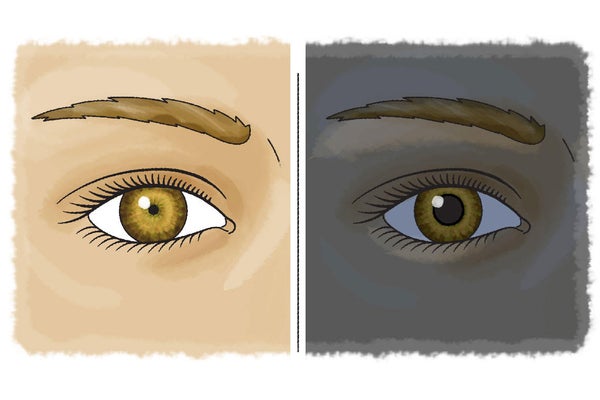

The pupil is the opening in the middle of the front of the eye that allows light to enter. Humans have round pupils. They appear black because light almost never escapes through them. The colored part around the pupil called the iris adjusts the size of the pupil. Its main function is to regulate the amount of light that enters the eye. In dim light the pupils dilate (open wider) so more light can enter. Switch to bright light and the pupils automatically contract. This is the result of a nerve signal generated in the back of the eye triggering the muscles in the iris. Because some nerve connections cross over to the other eye, both pupils contract in unison.

Materials

Flashlight that shines white light

Flashlight that shines red light (You can also hold a translucent red object such as a translucent red food container lid in front of the white flash to make it shine red light.)

Room with a bright light (such as an overhead light) that can also get dark (nearly pitch-black works best)

Markers, pencils and pens of different colors and a bag to carry them in

A volunteer or a mirror

Preparation

Before we start you need to know what the pupil of an eye is. Look your volunteer in the eye or look at your eyes in a mirror. The dark circle in the middle of the eye is the pupil. In this activity you will estimate the size of the pupils.

Put a few markers, pencils and pens in a bag, and bring it and your volunteer to a dark room.

Procedure

Allow your eyes to adjust to the dark for a few minutes. How is your vision in the dark (also referred to as night vision)?Can you see anything and, if so, can you recognize items? Can you describe them accurately?

Let’s test: Pick an object from the bag. Can you and your volunteer see well enough to say what the object is? Can both of you identify the object’s color?

Repeat previous step with another object from the bag. Are the results identical?

In a moment you will switch on the light and immediately look at your volunteer’s pupils or your pupils in the mirror. Do you think anything special will happen to the pupil?

Turn on the room’s bright light and quickly observe the pupils. How large were they when you just turned on the light? How large are they when the light is on for a while? Why do you think this change happens?

How do you rate your vision when there is plenty of light? To test this, take an object from the bag and hold it in the light. Can you recognize it? Can you see details such as its color?

Turn the light off and let your eyes adjust to the dark.

Turn on your flashlight on the white light setting. Hold it close enough so that you can clearly see your volunteer’s eyes, but take care not to shine the light into them or look directly into the beam of light. What happens to the pupil size when you turn on the light?

How well can you see what this white beam of light is illuminates? How well can you see what is not directly in the light beam?

To test, take an object from the bag and hold it in the light. Can you recognize it? Can you see details such as its color? What happens when you hold it away from the beam of light?

Repeat the previous four steps, but instead of a white beam of light choose a red light beam. Do you expect your vision will be different when you have a red beam of light instead of a white one? If so, how and why do you expect it to be different?

Extra: Find an adult to accompany you on a night outing to an area where there is very little light pollution. How easily can you do a night walk with your flashlight off, with it on the red-light setting and with it on the white-light setting? How is the experience different? Does the number of stars you can observe depend on the color light you use?

Extra: By wearing an eye cover over one eye while exposing the other eye to bright light, you can investigate how bright light in one eye changes the pupil size of the other eye. Do both pupils work in unison when they contract or expand or does it happen independently?

Observations and results

Did the pupils expand when exposed to a low-light environment and contract when there was plenty of light? Were you able to recognize objects in dim light but unable to recognize their colors? That is what our eyes are designed for.

Pupil size changes to optimize vision in a large range of light conditions. When there is bright light a smaller opening in the eye—or a smaller pupil—protects the back of the eye from getting damaged. In dim light the pupils dilate to allow as much light in as possible. That is why you see the pupils change size when light conditions change. Red light, however, does not trigger pupil contraction as much as other colors of light, making a red flashlight ideal for enjoying the night landscape.

Light-sensitive cells in the retina at the back of our eye allow us to see. The human eye has two types: cones and rods. Rods are extremely efficient; a tiny amount of light can trigger them. They are responsible for our night vision. They detect lines, contrast and movement—but they cannot distinguish color. The cones are responsible for color vision but they need plenty of light to activate. That is why in dim light conditions you could recognize an object but failed to detect its color.

More to explore|

Pupils Dilate or Expand in Response to Mere Thoughts of Light or Dark, from Scientific American

Rods and Cones of the Human Eye, from Arizona State University

Be Seen in the Dark, from Scientific American

Put Your Peripheral Vision to the Test, from Scientific American

Science Activities for All Ages!, from Science Buddies

This activity brought to you in partnership with Science Buddies